Olivia Vinall in Tom Stoppard’s The Hard Problem

Olivia Vinall in Tom Stoppard’s The Hard Problem

The last thing I want to see at the movies is a play — not an artful cinematic adaptation such as A Streetcar Named Desire, Glengarry Glen Ross or Doubt but a camera planted in front of actors and filmed with a live audience, replete with coughs, chortles and applause.

When the smell of popcorn wafts through the theatre, all around me there’s the sound of soft drinks being slurped (and waistlines expanding) and the coming attractions roll, I’m psyched, indeed, cine-psyched. I’m ready to be whisked off to another world, pushed along by swooping cameras, heartbeat-quickening editing and soaring music.

However, my prejudice against recorded plays has been shaken up by the mouthwatering line-up for this season’s National Theatre Live, which boasts so many top-drawer British stars in classic works you’ll be tempted to forgo that credit card-straining, culture- vulture trip to London and winter at home.

On offer is Hamlet with Imitation Game Oscar-nominee Benedict Cumberbatch in the role of the suicidal philosopher-prince; another Academy Award nominee, 12 Years A Slave’s Chiwetel Ejiofor, stars in an update of the medieval masterpiece Everyman; Tom Hiddleston (aka Loki in Marvel’s Thor series) is taking on Coriolanus; and Ralph Fiennes lets rip as the firebrand free- thinker Jack Tanner in George Bernard Shaw’s Man and Superman.

And if that’s not enough to lure movie buffs from the latest bit of Marvel mayhem or wrench the remote from couch potatoes, there is an encore showing of The Audience, in which Helen Mirren once again impersonates Queen Elizabeth II in a history-skimming chat show about the monarch and her prime ministers written by Peter Morgan (The Queen) and directed by Stephen Daldry (Billy Elliott, The Hours).

Esteemed actors in classic plays or, in the case of The Audience, a vehicle for a great star is one thing; a new work by a major playwright is quite another, as is the case with this year’s stand-out production, Tom Stoppard’s The Hard Problem.

It gives this new form of watching theatre great significance because we are unlikely to see a live performance of The Hard Problem because Stoppard is almost never staged here.

After a pair of historical-cum-political works, The Coast of Utopia trilogy (2002) and Rock’n’Roll (2006), Stoppard has returned to the playful philosophical comedies of his early and middle years, such Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (1966), Jumpers (1972), Travesties (1974) and Arcadia (1993), his last major hit.

In this latest intellectual boxing match, Stoppard pits a vivacious psychologist and believer in a higher power against a battery of scientists who are convinced everything we believe to be unique in mankind — altruism, love, faith, sorrow, even consciousness — is the product of biology.

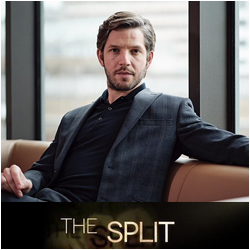

For the next two hours Hilary (beautifully played by Olivia Vinall) argues persuasively that consciousness does not simply spring from “a vast assembly of nerve cells” (to quote Francis Crick) while the materialists, among them her former teacher and boyfriend Spike (Damien Molony) mock her clinging to pre-Darwinian ideas. In the meantime, the hedge-fund billionaire who set up the lavish institute where Olivia does her research (“It has a gym!” as characters keep reminding us) reveals he is not the philanthropist he likes us to believe. Rather he is using the findings to exploit the stockmarket, predicting how people will behave when faced with turmoil and risk.

While the meat of the play is the scientific and philosophical debate about the nature of consciousness (“the hard problem” of the title) the heart is a sub-plot involving the young Olivia giving up her child for adoption so she could pursue her studies.

She talks about altruism but this act was as self-interested as the value-less materialists she criticises.

Reviews for The Hard Problem have been mixed, with some critics complaining Stoppard hasn’t created fully rounded characters but mouthpieces for scientific and philosophical positions, and others arguing that the debate is shallow.

And, certainly, on a single viewing The Hard Problem does not feel like top-drawer Stoppard. It lacks his signature wordplay and too much of the drama is carried by dialogue, with one strand, dealing with the financial crisis and the greed of the super-rich, undernourished.

However, I have a feeling that The Hard Problem will yield greater insights on a second viewing, with Stoppard, who is now 77 and more serious than the Wildean wit who exploded on to the stage with Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, probing serious issues about the nature of man as we sit on the cusp of artificial intelligence.

Indeed, the younger generation which flocks to eye-popping films about A.I. such as Ex Machina could learn a thing or too from a man who wields the most devastating special effects of all: the punch and counterpunch of two clever, articulate people.